Times are uncertain for a lot folks right now, and it is hard sometimes not to focus on what that means, for ourselves and for others. This is because all of us have at least some connection to the crisis, whether we are frontline workers (heroes), adjusting to working from home, or out of work altogether. Whether we are homeschooling in a suddenly full household or virtually isolated in our living space, we are all adapting to a new world with scary undertones, and that’s not even mentioning those of us that have contracted covid-19. Some of us are living in a near constant state of hyperfocus, agitation and worry, and even if you are currently immune to that, we are all in need of some pleasant distractions.

To all of that, in walks (or paddles) “Big Muddy” Mike Clark, of St. Louis’ only Mississippi River guide service and outfitter, Big Muddy Adventures.

CHECK OUT MY OTHER ARTICLE ON MY 2016 FULL MOON PADDLE WITH BIG MUDDY ADVENTURES HERE.

Mike is one of those big personalities, which makes what he does for a living the perfect career choice. He is as at home telling big stories, as he is living them, and if you’ve ever seen him in front of a group of enthralled kids, then you know he has a big heart too. His crew is the same way. The BMA team are all definitely out to shape experiences more than to turn a buck.

When I found out about the unique path he was navigating to raise money for the Gateway Resilience Fund, I can’t say that I was surprised (amused, yes). I was interested to learn more though, so last Wednesday, I called Clark up to get the scoop. A summary of our conversation is below. Note: story time with Mike is an adventure in itself, so I’ve tried to preserve his manner of speaking and colloquialisms as best as possible.

KAMP: Starting off, what is the Gateway Resilience Fund, and why do you think it is important?

MC: From my understanding, a number of small businesses, restauranteurs, and other folks spearheaded by Roo Yawitz (Mike’s partner in BMA), Gerard Craft and others, saw what was coming in terms of closures, and they got out in front of it by connecting with the St. Louis Community Foundation, one of the larger philanthropic organizations here in St. Louis. Basically, the idea behind the Gateway Resilience Fund itself is to get money quickly into the hands of the service [and] hospitality [industry]- chefs, bartenders, servers, the whole gamut of people who work for tips, and many of whom live check to check. So, as soon as these closures occurred, many of these people had no wherewithal to even go ahead and buy groceries and so on. The idea behind the Gateway Resilience Fund was to raise enough money to give grants to individuals and to also small businesses in this sector, to help them until the government money, which I understand has been promised, comes into effect (and things like unemployment and all that). Anyway, that’s a longwinded way of explaining what I understand it to be.

KAMP: How can people support the fund?

MC: Well, [they can] go directly to the Gateway Resilience Fund website, click on it, and I believe, that makes direct donations into the Fund possible. Note: here is the donations link.

Mike’s camp.

KAMP: Getting into what you are up to, so you’ve been living on an island in the Mississippi, is that right?

MC: Yeah, mm hmm.

KAMP: Why and how long have you been there?

MC: Well, this is day 20, and I came out here for a couple of reasons. One, the nature of my work with Big Muddy Adventures is to guide and outfit for individuals that want to experience nature on the great rivers. So, annually I do some type of expedition in which I’ll paddle in the vicinity of St. Louis, on the great rivers and others, and do some exploring and [generally] prepare for the season. I also do some distance learning education projects with select students and teachers during that time, so this was the time of year when this [pandemic] hit, when I would be doing that, just prior to opening our guiding season. Instead of doing something along the lines of a moving expedition, where I paddle and move everyday, it just crossed my mind to come and remain on the island. So, it’s day 20, and I am here until the coast is clear for everybody.

KAMP: Our weather hasn’t exactly been warm and sunny this whole time, has camp life been easier or more difficult than you’d planned?

MC: Well, two things, Jason. Number one, I am a professional at this. I do multi-day trips with groups of people, students and individuals, in which we paddle on these great rivers, and camp on islands, such as this. So, you know, I have the gear, I have 20 years of experience, and it is early spring here, so I expect weather to fluctuate. I made the joke the other day that, if you were to look at a graph of the weather, and I’m talking temps and precipitation, over the [last] 20 days, it would look like a roller coaster. And, that’s just the way it is in the Spring, so I don’t necessarily pay much attention to the forecast because I am prepared for whatever weather occurs. Like today, it’s 90 degrees out here, but I expect by Saturday, that will be drastically different. So, you know, it’s all about having a [good] camp- choosing a place, a campsite, which is protected from heavier storms and weather, or winds and stuff like that. That’s one, and you know, lot’s of firewood because I don’t use a cooking stove; I cook by fire. So, choosing the campsite is really important, and number two is, again, having the right gear.

KAMP: Swinging now to your background, how many miles have you logged on rivers at this point?

MC: You mean on this trip?

KAMP: No, just in general, throughout your years of paddling and adventuring.

MC: Yeah. Honestly, I’ve never, you know- I keep what amounts to a captain’s log, which after each trip, I sit down, or each day of each trip, I’ll sit down early in the morning, and I’ll write somewhat of a journal. Basically, making notes about water levels and particular places along the river or rivers, and making notes about whether there is something different about that place that I noticed, that I hadn’t seen before. And that becomes a cumulative base of knowledge, from which I can guide and teach. So, I really honestly don’t have a kind of spreadsheet log of my miles, but I’m well over 10,000. I’m guessing that I’m pretty well approaching 20,000 miles of paddling at this point.

KAMP: What is Big Muddy Adventures, and how did it start?

MC: Big Muddy Adventures came to life in 2002 as my particular, small business startup. The first thing that I did, however, was in 2001, and it wasn’t Big Muddy Adventures, as it is today. But in 2001, I was a school teacher in Chicago, and had moved just that year down here to St. Louis with my wife and kids. As a school teacher in an inner-city, urban area, I was pretty frustrated, and so I decided that I would paddle the length of the river, creating a virtual, distance learning schoolhouse (this was 2001 now), and I would develop a curriculum, along with other teachers that were interested, at that point. And we would deliver that curriculum while we were on our journey and connect with all of these students that way. That’s how Big Muddy Adventures started. It was an education initiative. Then in 2002, I partnered up on the same deal, the length of a great river expedition to again teach virtually and distantly. That trip was on the Missouri River with my great friend and river comrade, John Ruskey, down at Quapaw Canoe Company. He had already established this guiding and outfitting company down in Clarksdale, Mississippi in 1998 or 99. And so, on that journey of three plus months, just being 20 feet apart from one another, and all that, we had many, many conversations. The virtual schoolhouse/distance learning was successful, in terms of numbers, number of students and all that, but I felt very strongly by the end of that one that I was not teaching it [the way I wanted to]. Basically, I was producing [content] for students, and that was not all what I wanted to do. I really wanted to engage with students in a way that was not in a classroom with walls. Anyway, John walked me into a world where the virtual is cool, but there is really, really powerful things in getting people, especially kids, out on these rivers. To do it safely, to let them experience nature in this powerful place, and engage their curiosity. So that’s when the guiding part of it kicked off, it was 2002.

KAMP: Gotcha. I think that here, in particular, we have this great waterway, or rather this convergence of waterways, and yet, as a city we are somewhat disassociated from the river in many ways. People don’t really think about it in terms of something that you interact with. They see it at the riverfront, under the Gateway Arch, but beyond that, at least before your venture, I don’t know that most people realized that they could go out on it. Did you get that sense?

MC: Yeah, uh, two things, and I’ve expressed this often, as have the whole Big Muddy Adventures Crew. Everyone’s coming to recognize, especially now that we’ve put thousands of people out on these great rivers here and the connection between the river and these individuals has started to dispel it, what is a civic myth. And that myth is: if you go down and engage with this river, I mean, literally [some] people in St. Louis think that if you even go near the river, you are going to either die, or get sick, or something terrible will happen. That is just not true, ok? That said, this is not where novice paddlers should go, you know? This takes experience, and the right boat, and all of that. Otherwise, it could be dangerous. That’s it. That’s it. This civic myth though has been propagated over a 100 years. [Though] the other side is- think about it, we have been paddling canoes for 5,000 years on these rivers. This isn’t, “Oh, we [BMA] just invented this idea of paddling on the Mississippi and Missouri River!” That’s, uh, no. In fact, the native word for the Missouri River translates directly to “river of big canoes”. Note: a St. Louis Post-Dispatch article from 2007 offers that the word, “Oumessourit”, meant “people of the dug-out canoes”, but that’s splitting hairs.

So that’s one, the civic myth that’s just been there to some extant and we are breaking it down. The second thing that, I guess, I would have to say is that the interaction of people in our region with the rivers is every day, multiple times a day. Just turn on your tap and drink this water. Or flush your toilet. Or watch the rain go down your spout and into our sewer system. We are completely disconnected as humans from that thing, the river, and yet, our very existence is tied to it. So, as an environmentalist, I really do believe that, you know, that we are responsible as humans for caretaking the resources that we have and use, and this river is paramount as a resource here in St. Louis.

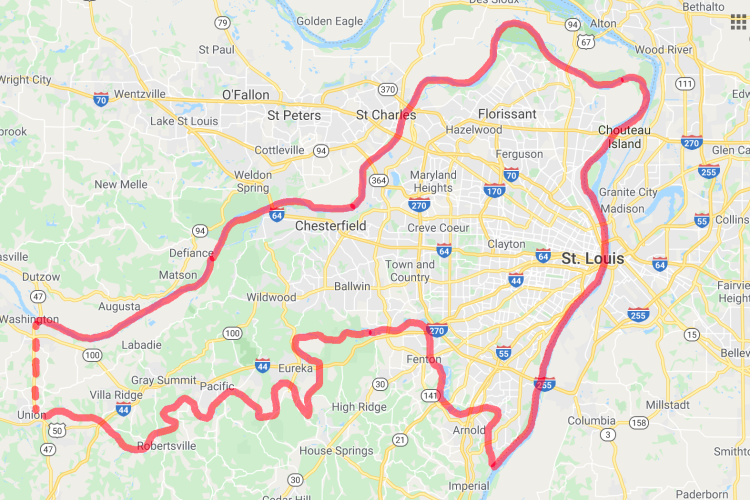

One more thing, and this is an interesting thing. I have circumnavigated, that is paddled a boat, or canoe in my case, around St. Louis five times (and that is what I was intending to do again this year). St. Louis is an island. Ok? If you take Google Earth and follow the Bourbeuse River [Brush Creek] from Union, it travels 18 miles downstream and meets the Meramec. It then travels 78 miles down and meets the Mississippi. [At] Washington, Missouri, which is the Missouri River, from there to the confluence is 69 miles. From the confluence of the Missouri and the Mississippi to the confluence of the Mississippi and the Meramec is 36 miles. So the only part I left out was between Union, Missouri and Washington, Missouri, and that’s 9 land miles. That’s it. That is it. And by the way, there’s two creeks- one going into the Mississippi watershed, one going into the Missouri. Those two creeks meet on a bluff line, or a rising hilltop, about two and a half or three miles outside of Washington, and they are within a mile and a half of each other. Literally, as far as water goes, there is only about a mile and a half or two miles separating the two watersheds. This is kind of a poignant time to think about living on an island, don’t you think? Right? That’s what I set out to do early on, before this crisis, this horrible covid pandemic, but you know, that wasn’t responsible of me to go paddling around the ring here, knowing that I would come into contact with human beings. I knew full well, 20 plus days ago, that we were all, very quickly, going to be in this position of stay at home, and absolutely take care of ourselves and our loved ones.

Mike’s St. Louis island

KAMP: You dubbed your island “Quarantine Island”, what made you choose that name? Note: I wondered if perhaps the name was a nod to the former Quarantine Island, actually several islands of various names, near St. Louis that were used to quarantine cholera (and other) patients in the 1800’s.

MC: I am in the demographic of those that really should not get this virus. You know? I really am. I’m 60 years old, ok? I’m a healthy man; I’m physically fit. I knew though that I was going to be told that I couldn’t visit my family. My parents are still alive, God bless them, but I wasn’t gonna go visit them. I wasn’t even going to necessarily visit my boys, or anybody else for that matter, so essentially, I knew I was going to be quarantined. And so I thought, well, I hate feeling helpless. I’m not one of those guys. I want to dive into things, trouble and otherwise. I want to use skillsets that I’ve acquired to help people, and it was clear that I wasn’t going to be able to do that. I mean, I’m not a medical professional, and I’m not a firefighter or a police officer, or anything, so I didn’t see anything but sitting around the house with a dog. I figured, well, I could come out here to the island, and quarantine myself. And that’s how it got to be. I just came out here and said, alright, I’m going to hunker down. At that point, when I told Roo and the gang, “Hey, I’m not circumnavigating St. Louis as originally planned. I’m going to go out on an island and stay.” They said, “Hey, let’s raise some money for the Gateway Resilience Fund.” I said, “That’s fine. I can’t organize that though; I don’t know what to do with that.” But they did, they just put it up there on social media and said, “Hey, if you want to have some fun with this, AND give to a very good cause, pledge a dollar a day, or whatever, for every day he stays out there.” I was pretty sure no none [that was pledging] knew about how long this was going to be. I’m fairly certain though that the ‘coast is clear’ thing ain’t coming for quite a while. I’m cool with it. You know? I’m fairly comfortable out here. My days are organized and ordered, and there’s chores, and the simplicity of life is- you know, just really living close to the earth, in so many ways, is just really psychologically healthy. And the fact that I can send out some goofy posts or whatever as a distraction in some way, or just something other than the continuous droning on of politics and fear and anxiety, and honestly, bullshit, you know? We know there’s enough bullshit being passed around to drown everything.

In all honesty, when I did my first expedition, and adventure learning project over the length of the Mississippi River, I left Lake Itaska on September 4th, 2001. On September 11th, I was in the Headwaters, completely disconnected. We had a satellite phone. Cellphones weren’t- I mean, they were around, but you could only get coverage in Minneapolis, St. Louis, Memphis, you know? There wasn’t coverage. You were literally disconnected except for this very expensive, satellite phone, and that was what we were using to send out this package of data and information into this education initiative. And we were doing it on a daily basis. So, September 11th, we are in the Headwaters, a very remote area of the Mississippi River, and 9/11 hits, and we don’t know about it until September 12th. Now imagine that, where on the frickin’ Earth could you be and not know about 9/11 on 9/11? You’d have to be in a pretty remote place, which we were. So anyway, on September 12th, I called home because we pulled in- we crossed a lake that morning, the 12th, not knowing, after a pretty tough paddle across a pretty tough section of this river and we end up at the mouth of this lake, where it becomes a river again, and there is an Army Corps of Engineers campground there. Right at the mouth. And there were 30 RVs with the typical folks that RV and all that (retired folks). And they were all of them gathered around a couple of RVs that somehow had one of those early, digital satellite TV hookups. We pull up in a canoe, looking like “what the hell is everybody doing?” And I walk up and I see the towers going down, which had been on a reel (that’s all anybody saw, for I can’t even tell you how long that was). So anyway, I’m like, “Oh, holy shit!” I call home on the sat. phone immediately, “Hey baby, I just found out about this.” And she was just beside herself. And I’m like, “Hey, here’s the problem: I can’t leave here right now. Logistically, it is going to take something to get me, and Dave, and Eric, and all of our gear and everything, and also suspend this expedition that has 15,000 students logged in.” It was going to take, a few days. Well, so immediately we send out an email to all of these teachers, and schools, and everything, and said, “Hey, literally, we just found out about this. This is horrifying; we get it. We will suspend this expedition, and we hope everyone is safe.” Immediately, emails start coming back. Immediately. Teachers, parents: “Don’t! This is what the kids have to get their heads away from the towers falling and the extreme fear and anxiety. Don’t suspend the expedition. Please keep going. Please keep delivering. This is what the kids need. It is their only distraction.” Well, holy shit…

Now, so I come out here as this [pandemic] hits, well, I come out here as it’s hitting, and I say, “Oh, well, I have some experience to draw upon.” And I’m not talking about the distance learning and all of that. You know? I’m talking about sending a daily little picture and a funny-ass video of me shooting hoops, or me howling at the moon. And I have [the] experience that this is a [necessary] distraction. This is something other than the anxiety, the fear, the boredom, and the bullshit that this is causing. So that’s it, that’s my- well, you got it all. That’s my passionately, I… I hear my voice rolling back in sort of passionate ways about this. My humility is very much intact out here, Jason. Honest to God. You know, I am, I… I in no way, shape or form want to diminish what any single person is experiencing at this time. I don’t. My very own parents are stuck in an independent living [facility], in Chicago, and it’s horrifying. They get their meals [given] to them from outside the door. They cannot come out of a one bedroom, independent living apartment on the 10th floor [of a building] on the northwest side [of Chicago]. You know, and I couldn’t even go visit them if I wanted to. So, yeah, my humility is intact, man.

Quarantine Island

KAMP: I hope that you are hearing those voices from long ago saying, “We need you to keep going right now.” The distraction is definitely more important than the word ‘distraction’ truly conveys.

MC: It’s not the word that I want to use. Alright? You know, some sort of egotistical mannerism that I have would like my experience out here to be… not just a distraction. But really, as a retired schoolteacher, this is a form of how I can educate- meaning, hey, we all have had to simplify our lives to some extant. Right? And boy, it doesn’t get more- it doesn’t become more clear how simple life can be than living in a tent on an island, cooking by fire. And you know, using good conservation of resources. That’s it. So maybe there is an element of being an educator.

Also, it’s really cheap living out here! I turned off the electric at the house- no need, right? I turned off the WiFi that was in the house. I told waste management, “Suck a bark. Don’t pick up, there won’t be any trash here. Don’t bill me.” I mean, my literal expense, other than insurance, is the phone. That’s it. Given how things are, I was going to get down to this one way or another anyway, you know? The cost of living doesn’t change, but the income sure does.

KAMP: On that, while you are providing us with education and lot’s of inspiration, and raising funds at the same time to help support St. Louis businesses and individuals that are in need, or will soon be in need, I am sure that your business is also being impacted. How can people support BMA right now?

MC: You know what? I’m going to say (you know Roo would say it, too) Big Muddy Adventures has experienced- last year, we had the third highest flood stage in the history of recorded crests, we had the longest duration of flood stage in the history of keeping records of floods, [and as a result] we could not open our guiding season until July. And the year previous to that, the floods of September topped the top ten crests and shut down the end of our season. So, we have experience [with crisis]. The problem though is that a flood has some sort of predictability in terms of when it will end, to some extant. You know, there is some legitimate forecasting you can use to look at it. Coronavirus? Not so much. But, Big Muddy Adventures, and Roo, and the whole crew, are very, very creative. We’re very dedicated to the mission that we have, and so if people want to support Big Muddy, then [they] could certainly go ahead and buy a gift certificate for one of the full moon trips in July or August or September, and if by June, we know that ain’t gonna happen, then you get your money right back. Anything like that would help to just pay the ongoing bills of Big Muddy Adventures, but I honestly think that it is more important right now to support the Gateway Resilience Fund. Nobody in the service industry has experience with this [level of catastrophe].

If you would like to support BMA with a certificate for a Full Moon Trip, more info is available here.

Great article Jason.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mike!

LikeLike